Latest

News

Aims

of the Society

Membership

Past

Journals

Contact

Us

Interesting

Links

Auction Activity

Recommended Reading

Home Page

Events

Collectors Club

Journal Index

Book Offers

|

Sample Journal Articles

CHARLES LUCAS – THE FIRST VC

By Brian Best

Three men can

claim to be the first VC in that elite list of recipients of the world’s

highest award for outstanding gallantry. The name of Lieutenant Cecil Buckley

RN was the first to be published in the London

Gazette of 24 February, 1857 for his part in two exploits in the Sea of

Azoff

on 28 May, 1855. Due to his superior rank, Commander Henry Raby RN was the

first man to physically receive the Cross at the inaugural investiture on 26

June, 1857. This was awarded for his part in bringing in a wounded soldier

under fire during the abortive attack on the Redan , 18 June, 1855. (see cover

of 4th edition of The Journal)

The man who could genuinely be said to be

the very first VC, however, was a young Irish midshipman named Charles Lucas,

whose gallant act was performed on 20 June 1854, in what was virtually the

first action of the war against Russia.

He was born into a wealthy landowning family on 19 February 1834 at Drumargole,

County

Armagh. At the age of fourteen, he

joined the Navy in 1848, the year of the Irish Potato Famine. He first served

aboard HMS Vanguard, but it was in

his second ship, the 40 gun Fox, that

he saw his first action in the Second Burmese War of 1852.

Under the command of Commadore G.Lambert, Fox was part of the small squadron that

attacked the heavily fortified enemy town of

Martaban to great effect. Led by Commander

Tarleton of the Fox, a landing party

attacked and captured the enemy stockades, spiking their guns and destroying

their ammunition. Further action followed against

Rangoon and Pegu. The end of the war resulted

in the annexation of most of Burma

to the East India Company.

With the outbreak

of war with Russia in 1854,

the greatest naval danger was seen as the Baltic Sea, where Russia’s main fleet and her

principle arsenals were situated. It followed that the main Anglo-French fleet

was sent to the Baltic, but any hope that the Russians would oblige with a set

piece naval battle was thwarted by the enemy’s refusal to leave Kronstadt,

their heavily-defended home port. The monotonous task of operating a blockade

was alleviated by the occasional raid against land targets.

Before war had been declared, the

Admiralty had the foresight to reconnoitre the Baltic area and despatched the

new steam sloop, Hecla. Midshipman, or Mate, Charles Lucas had

recently transferred to the Hecla,

which left Hull

on 19 February 1854. In a voyage of some 3000 miles, she carried a team of

surveyors, who drew charts and sought suitable anchorages for the large

Anglo-French fleet. Several times Hecla

used her superior speed to outrun Russian frigates, for she was better suited

to speed than fighting, something later her captain seemed to forget.

The Hecla’s

captain was the energetic and resourceful William Hutcheson Hall, a man who

would play a prominent role in Lucas’s life. As a young lieutenant, Hall had

commanded the East India Company iron steam ship Nemesis during the First China War of 1840. With its shallow

draught and armed with rockets, the Chinese called it the “devil ship”, as it

created havoc amongst the enemy junks in Anson Bay. Hall further came to the

Lordship’s attention when he, and two other like-minded officers, proposed the

establishment of a sailor’s home in Portsmouth.

When sailors were paid off, they were often far from home and fell easy prey to

all sorts of persons who were skilled in parting the unsuspecting victim from

his money. The idea of a sailor’s hostel gained approval and both Queen

Victoria and Prince Albert

added their endorsement and financial support. From this, there grew the highly

successful establishment, which gave sailor’s a refuge while waiting for

another posting.

When the Hecla returned from her Baltic mission, she joined the main fleet

at Dover. The

surveyors distributed their charts and briefed the commander, Sir Charles

Napier, and his captains. The fleet, including Hecla, then set course for the Baltic.

After the disappointment of the Russian

fleet’s refusal to fight, lesser targets were sought. It was Hecla, together with the Arrogant that first engaged the enemy

amongst the Aland Islands at the mouth of the Gulf of

Bothnia. Capturing the crew of a fishing boat, they compelled them

to guide them through the shoals and scattered islets to look for enemy

merchant ships, which they suspected were at anchor. The Aland

Islands were described by a naval officer as, “This granite

archipelago encloses a perfect labyrinth of straits and bays studded with minor

islands, and so fringed with reefs and banks as to make the navigation often

impossible- always hazardous.”

As they were negotiating a narrow

waterway, a Russian battery opened fire, but was quickly silenced by the 46 gun

Arrogant. The following morning, the

shallow draught, but lightly armed, Hecla

found herself in range of the guns of a Russian fort and, although she

returned fire, she was no match for it. Fortunately, Arrogant arrived in time and, despite running aground, was able to

silence the enemy guns. Finally, they found the three merchant ships, two of

which had run aground. The third was taken by Hecla who, under fire from shore batteries and Russian infantry,

took her in tow and steamed away with

her prize. In the process, one man was killed and Hall was wounded in the leg

by a spent musket ball.

This minor success received the thanks of

the admiral-in-chief as well as the British Government and no doubt spurred

Captain Hall to undertake a foolhardy attack against the formidable fortress of

Bomarsund on the east coast of the main island in the Aland chain. In what

should have been a reconnaissance led by Captain Hall, developed into a

bombardment by three lightly armed ships against the solid walls of the three

granite-built fortress towers and heavily fortified casements. The Russians had

considerable superiority in firepower with over 100 guns against just 38 (Hecla 8, Odin 16 and Valourous 16)

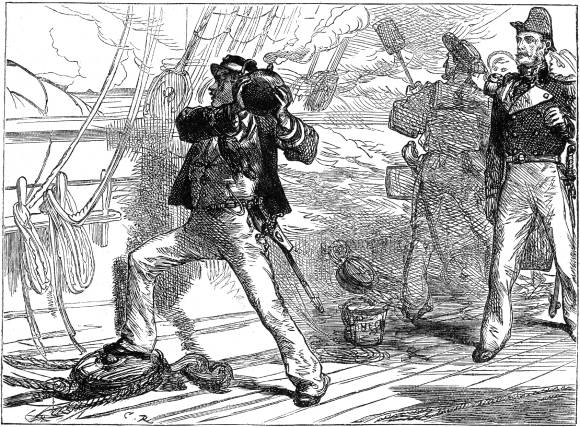

Early in the fight, a live shell landed on

Hecla’s upper deck. A cry went up for

all hands to fling themselves on the deck. One man ignored this advice. 20 year

old Charles Lucas ran forward, picked up the round shell with its fizzing fuse,

carried it to the rail and dropped it overboard. It exploded with a tremendous

roar before it hit the water and two men were slightly hurt. The consequences

would have been far more serious but for Lucas’s prompt action.

Captain Hall showed his gratitude for the

saving of his ship by promoting Lucas on the spot to Acting Lieutenant. In his

report. Hall was also fulsome in his praise for Lucas’s great presence of mind.

In turn, Sir Charles Napier echoed this praise and recommended confirmation of

Lucas’s promotion.

Hall also exaggerated the damage inflicted

upon the Russians and earned a stiff rebuke from the Admiralty for putting his

ship in unnecessary danger and expending all his ammunition to little effect.

None the less, the news was well received by a British public hungry for some

offensive movement from their much-vaunted navy. For a while, the name Bomarsund was the topic of conversation and a new coal mining village near Newcastle was even named

after this obscure Baltic fortress.

For his bravery in saving the lives of his

fellow crewmen, Charles Lucas was awarded a gold Royal Humane Society Medal.

This large 51mm dia medal was not intended for wearing, but Lucas had a ring

and blue ribbon fitted. In 1869, official permission was granted for the

wearing of the medal and 38mm dia medal was produced with a scroll suspension

and navy blue ribbon.

Just three years later, on 26 June 1857,

Lieutenant Charles Lucas stood fourth in the line of recipients at the first

investiture of the Victoria Cross and received his award from Queen Victoria (see first

edition of The Journal, Oct.2002).

Lucas did not see any further action but

steadily climbed the promotion ladder. He served on Calcutta, Powerful, Cressy, Edinburgh, Liffey and

Indus. In 1862 his was promoted to Commander

and then to Captain in 1867, before retiring on 1 October 1873. He went to live

with his sister and brother-in -law in the Western Highlands until he received a

summons to his death bed from his old captain, now Admiral Sir William Hall KCB, FRS,

who made an extraordinary request. He begged Lucas to take care of his wife

Hilare and to marry his only daughter, Frances. Lucas, an incurable romantic,

agreed. The marriage was not a success for Frances was arrogant and

violent-tempered and far too aware of her position as a member of the Byng

family. being the grand-daughter to the 6th Viscount Torrington. They married in 1879 and produced

three daughters.

They made their home at Great Culverden,

on the Mount Ephraim area of Tunbridge Wells. In 1885, Lucas was promoted to Rear-Admiral on

the retired list. He occupied himself as a JP for both Kent and Argyllshire.

After a train journey, Lucas found to his dismay that he had left all his

medals in the carriage. They were never recovered. Instead, he was issued with

a duplicate group. The IGS bar’Pegu’ is engraved with his details, as are both

gold Royal Humane Medals. The Baltic Medal is blank, as is the reverse of the

Victoria Cross.

Charles Lucas died peacefully at his home

on 7 August 1914, just as Europe plunged into

the madness of the First World War. He was buried in St Lawrence’s Churchyard

at the nearby village

of Mereworth

Lt. George Knowland

The Last Commando VC

By Robert J.Mewett

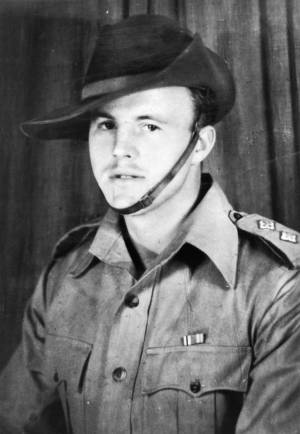

The above portrait * shows a fresh-faced young George Knowland, recently

promoted and proudly displaying his lieutenant’s pips. He wears a jungle

warfare cob hat and on his breast is the ribbon of the newly issued

Defence Medal. Tragically, he would never live to wear the crimson ribbon

of the Victoria Cross.

My late father, Bob Mewett, served with Lieutenant George Knowland during

the epic battle fought on Hill 170 in 1945. It has always been a

fascination to me as to what manner of man he was to perform such a

prolonged act of bravery.

The awarding of the VC from an outsider's point of view seems to be a

controversial affair for who is to say which act is braver than another or

which danger is the greater. It is undoubtedly true that many deserved VCs

have probably not been awarded and many brave acts have gone unnoticed and

unwitnessed. But from the soldier's side things are more straightforward.

Comrades who were there recommend VCs and appreciated the danger. The VC

winner is a soldier’s 'Soldier', the one every raw recruit aspires to when

they first enlist. He stands as their mentor and self image of a supreme

fighting man.

The VC is earned in the soldier’s dream but won in his worst nightmare.

The VC recipient is proudly claimed by his regiment and held up as an

example of what a soldier should be. But this, for those who are

interested in such matters as 'what manner of man' wins a VC, is where

confusion sets in. Many have won the ultimate award and have lived to tell

the tale and on enquiry these recipients have proved to be on the whole

ordinary and self effacing, disarming the questioner with such answers as,

'I only did what anybody would have done' or 'I don't see my self as

brave'. This is the point, for bravery is seen from the perspective of

those around the individual, and is very rarely, conceived by the

individual themselves.

Those who do survive seem to spend their future time eroding the event to

a more manageable size, rubbing the edges off and smoothing things over,

in order for them to shoulder the burden of this the highest of battle

field awards.

Strangely, living VC winners do not seem to be the place to look for the

answer of 'What Manner of Man?'

The pressures of winning such an award do not burden those who are awarded

the VC posthumously. We only left with a citation. An individual and an

action frozen in time and space never to be changed, just read and

interpreted by any one interested enough to want to.

A photo often accompanies citations. Only those few that don't carry an

image are the individuals condemned to remain invisible heroes. But some

citations border on the mundane and again unintentionally reduce the act

to almost everyday.

It seems to depend on how long after the action the citation is written

and how close the writer was to the original deed and their creative skill

in reproducing the facts. If you can have luck in such things we have it

in the highly detailed citation to Lt George Knowland.

EARLY YEARS

George Arthur Knowland was born in Catford in South East

London on 16 August 1922 and, after the death of his mother, he spent some

time in care at an orphanage. In the 1930s, he lived with his father in

Greenfield Road, Croydon and attended the local school, Elmwood Junior

School. As soon as he was old enough, he enlisted in the army in 1940 and

joined the Royal Norfolk's, later volunteering for the Commandos.

He was posted to No3 Commando and fought with them in Sicily and Italy.

Distinguishing himself in this theatre, he was promoted to sergeant. When

he returned home for officer training, he married Ruby Weston. In January

1945, he was sent out to the Far East to join No I Commando, which was now

resident in Myebon, Burma.

No 1 Commando had fought in North Africa on the Torch Landings and had

spent months of hard training in India preparing for the assault of the

Arakan Peninsular. George Knowland, now commissioned lieutenant, was

posted to 4 Troop as a section leader.

3 Commando Brigade, of which No.1 Army Commando were a part along with

No.5 Army Commando and 44 and 42 RM Commando, were given the task of

assaulting the Arakan Peninsular at Myebon. Here they were to take and

hold the dominant features of the southern Chin Hills. If they could

achieve this, they would cut off the supply and escape routes of the enemy

and secure the bridgehead.

HILL 170

No 1 Commando secured and dug in on a feature known as

Hill 170, code named ‘Brighton’, a half mile from the village of Kangaw,

with 4 Troop defending the most northerly end. It was the start of which

was to become an epic battle lasting 10 days. Finally, the Japanese

commander concentrated his numerically superior force of 300 against Hill

170 and the surviving 24 men of 4 Troop. An estimated 700 shells landed on

the hill on that last day of the battle. In a day of continuous fighting,

much of it hand to hand, the Commandos repulsed and counter-attacked the

waves of fanatical Japanese. Prominent amongst the defenders was the

newcomer, George Knowland, whose energy and bravery acted as an

inspiration to his comrades. This made him a particular target and he drew

heavy incoming fire, but miraculously he was unscathed.

He used just about everything he could lay his hands on the keep the enemy

at bay; grenades, rifle, light machine gun and even a 2 inch mortar, which

he fired from the hip against a tree stump. This use of a mortar was both

difficult and dangerous, as the recoil would have been considerable. At a

moment when the Japanese were only about 10 yards away, Knowland grabbed a

Tommy gun from a casualty and, standing up in full view, sprayed the

attackers until they fell back. At this moment of victory, he was mortally

wounded. The crucial ground, however, was never lost and the critical

position secured until re enforcements arrived.

When 3 Commando Brigade second in command, Brigadier Peter Young, arrived,

he noted, almost the first of our dead I saw was Knowland. He lay on his

back, one knee slightly raised, with a peaceful smiling look on his face,

his head uncovered.

Around the forward positions occupied by 4 Troop lay 340 enemy dead and a

further 2300 dead around the whole of Hill 170.

Citation in respect of VC award to Lt G.A. Knowland

War Office – 12 April 1945

The KING has been graciously pleased to approve the posthumous award of

the VICTORIA CROSS to: -

Lieutenant George Arthur KNOWLAND (323566), The Royal Norfolk Regiment

(attached Commandos) (London S.E.1)

In Burma on January 31, 1945, near Kangaw, Lieutenant Knowland was

commanding the forward platoon of a troop positioned on the extreme north

of a hill, which was subject to very heavy and repeated enemy attacks

throughout the whole day. Before the first attack started Lt Knowland’s

platoon were heavily mortared and machine gunned, yet he moved about among

his men keeping them alert and encouraging them, though under fire himself

at the time.

When the enemy, some 300 strong in all, made their first assault they

concentrated their efforts on his platoon of twenty four men, but in spite

of the ferocity of the attack, he moved about from trench to trench

distributing ammunition, and firing his rifle and throwing grenades at the

enemy, often from completely exposed positions.

Later when the crew of one of his forward Bren guns had all been wounded,

he sent back to troop HQ for another crew and ran forward to man the gun

himself until the crew arrived.

The enemy was less than ten yards away from him in dead ground down the

hill, so, in order to get a better field of fire, he stood on top of the

trench firing the light machine gun from the hip and successfully kept

them at a distance until a medical orderly had dressed the wounded men

behind him.

The new Bren team became casualties on the way up, and Lt Knowland

continued to fire the gun until another team arrived.

Later when a fresh attack came in he took over a 2inch mortar whose team

had been ordered to the forward trenches to replace casualties, and in

spite of heavy fire and the closeness of the enemy he stood up firing the

weapon from the hip and killing six of the enemy with his first bomb. When

all bombs were expended he went back through heavy grenade mortar and

machine gun fire to get more, which he fired in the same way in front of

his platoon in the open. When those bombs were finished he went back to

his own trench and continued to fire his rifle at the enemy. Being hard

pressed and with the enemy closing in on him from only 10 yards away he

had no time to recharge his magazine. Snatching up a Tommy gun of a

casualty he sprayed the enemy and was mortally wounded stemming this

assault, though not before he had killed and wounded many of the enemy.

Such was the inspiration of his magnificent heroism, that, though fourteen

out of twenty four of his platoon became casualties at an early stage, and

six of his positions were over¬run by the enemy, his men held on through

twelve hours of continuous and fierce fighting until reinforcements

arrived. If this northern end of the hill had fallen, the rest of the

position would have been endangered, the beach head dominated by the enemy

and other units inland cut off from supplies.

Not suprisingly, No.1 Commando was honoured with many gallantry awards, of

which Knowland’s was the highest. In addition, there were 2 MCs, 2 DCMs

and 13 MMs.

Knowland’s VC was received by his widow, Ruby, who handed it on to his

father, now a publican. For many years it was proudly displayed in his

Finsbury pub but, in 1958, it was stolen and has never been seen again.

George Knowland’s body was buried at Taukkyan War Cemetery, 20 miles north

of Rangoon. On 9 May 1995, a brass plaque was unveiled by the late Captain

Philip Gardner VC to the eight VC recipients, including Knowland, from the

London Borough of Lewisham.

On 31 January 2002, George Knowland was further honoured by his old school

in Croydon. Through the efforts of Michael Lyons of the British Legion, a

handsome plaque has been placed in the hall at Elmwood Junior School and

was unveiled by Countess Mountbatten.

Subsequently, the Commando Association contacted the school's head

teacher, Heather Jones, and together formulated an annual award to be

given on 31 January, to mark the anniversary of Knowland’s death.

The George Knowland Certificate of Merit will now be presented to the

Elmwood pupil who exhibits the lieutenant’s example of selflessness.

Editor’s note)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Harry Winch (2 Troop), John Huntington (3 Troop), Charles Hayes, Vic

Ralph, the late Bob Mewett (4 Troop), Henry Brown MBE, ORSM…all veterans

of Hill 170. They also served: John Lowman (4 Troop),

Pete Dovey & Roy Nicholls (5 Troop)

* Photo portrait reproduced with kind permission of the Imperial War

Museum, ref. HU2031

Artist’s impression of Lt. George Knowland defending

Hill 170, with kind permission from the 1st Battalion the Anglian Regt.

THE UNVEILING AND DEDICATION OF THE VICTORIA CROSS AND GEORGE CROSS

MEMORIAL, WESTMINSTER ABBEY, 14 MAY 2003

by John Mulholland

On 14 May 2003, HM The Queen paid special tribute, on behalf of the

nation, to recipients of the VC and GC when she unveiled the first

national memorial at Westminster Abbey. The decision to place the memorial

stone in the Abbey followed an eight-year campaign by the VC and GC

Association. Although there are many memorials to individuals and groups

of VC and GC recipients, until now there had been no national memorial to

honour them collectively. The memorial ledger is engraved in nabresina

stone, with enlarged bronze and silver crosses, inlaid with enamel

ribbons. Beneath is the simple inscription: "REMEMBER THEIR VALOUR AND

GALLANTRY."

The Queen was accompanied by HRH The Duke of Edinburgh and the service was

attended by over 1,600 guests including 11 of the surviving 15 VC holders

and 23 of the surviving 29 GC holders. The recipients attending the

service travelled from Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, India,

Malaysia, South Africa and the USA.

Guests began arriving at the Abbey from 9.00 am onwards and there was

strict security with armed police manning the security booths at each

entrance. By 10.00 am there was a large traffic jam outside the Abbey as

roads nearby were cordoned off. Outside the Great West Door there was a

tri-service guard of honour and inside an array of flags of nations

representing recipients of the VC and GC. The Queen and The Duke of

Edinburgh were received at the Great West Door by the Very Reverend Dr

Wesley Carr, Dean of Westminster, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Sir

Tasker Watkins VC GBE DL, Deputy President of the VC and GC Association.

The service began at 11.00 am with Fanfare for a Ceremonial Occasion

played by the Fanfare Trumpeters of the Royal Marines. During the opening

hymn, The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh took their places. The bidding

was made by the Dean, followed by prayers and the first reading from

Romans 12:1-9 by Lt. Cdr Ian Fraser VC DSC RD*, Vice-Chairman of the VC

and GC Association. The Choir then sang Psalm 67.

The next reading from The History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides

(circa 400 BC) was an inspired choice. It was read by Colonel Stuart

Archer GC OBE ERD, Chairman of the VC and GC Association. The passage from

Pericles' Oration over the Athenian Dead, included the lines: "No, they

joyfully determined to accept the risk. Thus choosing to die resisting,

rather than live submitting, they fled only from dishonour, but met danger

face to face, and after one brief moment, while at the summit of their

fortune, escaped, not from their fear, but from their glory."

Colonel Archer then invited The Queen to unveil the Memorial, which was

placed on a specially designed stand and covered with the Union Flag.

After the unveiling the Queen said: "Mr Dean, to remember the valour and

gallantry of all holders, living and departed, of the Victoria Cross and

George Cross, I ask you to receive this memorial into the custody of the

Dean and Chapter, and invite you to dedicate it." Following the dedication

the congregation stood for the stirring Antiphon which was specially

commissioned for the service.

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, then delivered a sermon

and argued that bravery was not simply a wild disregard for danger. "The

conduct of war relies on many kinds of bravery… and often behaviour in war

or in crisis is so mixed that it is hard to tease out real virtue from the

courage of temperament or madness", the Archbishop said. But there was

more to bravery than heroic insanity: "Courage of heart and mind comes not

just from patriotism, but from conviction that a country is committed to

justice and freedom; not just from obedience to orders or to some abstract

duty, but from a sense of the human worthwhileness of comrades and

colleagues and, simply, other human beings." The Archbishop concluded that

the type of courage displayed by the holders of the VC and GC was of a

selfless nature: "Courage as a true virtue is the kind of courage that

reflects the bravery of Christ, courage that does not deny the reality of

fear but is moved and energised by a vision," he said. "It is always

courage that is exercised in one way or another for the sake of others, to

make something possible for others, not for personal gain or glory."

A soldier, sailor, airman and a policeman then carried the newly dedicated

memorial to its site close to the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior. The party

was preceded by the flags of the representative nations and four holders

of the George Cross: Michael Pratt, Alf Lowe, Tony Gledhill and Derek

Kinne. Four holders of the VC immediately followed the memorial: Lt Cdr

Ian Fraser, Keith Payne, Flt. Lt. John Cruickshank and Capt. Rambahadur

Limbu. At the rear were the Verger, the High Commissioner for Malta, the

Dean's Verger and the Dean. Whilst this procession slowly moved down the

nave, the choir sang an anthem from The Pilgrim's Progress by John Bunyan.

The congregation stood and faced west for the Act of Remembrance and the

notes of the Last Post resounded around the Abbey. The Last Post caused

some, in an otherwise stoical congregation, to dab their eyes in memory of

departed relatives and friends.

The High Commissioner for Malta gave the exhortation to which the

congregation said, "We will remember them". During the silence the stone

was placed close to the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior, near the Great West

Door. After a faultless Reveille, the procession returned to the Quire and

Sacarium whilst the congregation sang He who would valiant be. The prayers

were adapted from a collection selected by the late Rev. Geoffrey Woolley

VC OBE MC. The closing hymn was Now thank we all our God, followed by the

blessing and the National Anthem.

To anyone present it was clear that much thought and preparation had been

given to the service and everything appeared to go to plan. Those in the

congregation had the benefit of video screens to view the proceedings.

Unfortunately, for some, the view was marred by the headress of some

ladies in the congregation - a similar problem was reported by The Times

at the first VC investiture in Hyde Park on 26 June 1857. Also the sound

system in the Abbey had its problems so that in certain parts of the

service, notably the Archbishop's sermon, echoes caused an indistinct

sound. But these problems were minor in comparison to the spectacle of

such a momentous occasion - the most important gathering of VC and GC

holders and relatives since the 1956 VC centenary celebrations in London.

Each member of the congregation received an Order of Service and a

memorial booklet, which listed all recipients of the VC and GC and a list

of donors to the memorial. At the end of the service most of the

congregation filed past the memorial and left by the Great West Door.

After the service many of the guests attended a reception at Westminster

Hall. They walked past the North Door of the Abbey on a cordoned off

pavement on Broad Sanctuary. The traffic was diverted around Parliament

Square because Margaret Street (opposite the Palace of Westminster) was

shut to traffic to allow the guests across the road to Westminster Hall.

Many guests were in uniforms or suits wearing their full size medals. Some

guests wore their relatives' VC groups or miniatures on their right

breasts. Members of the general public were cordoned off behind barriers

at either end of Margaret Street and a large police presence ushered

guests towards the security gates where invitation tickets were shown to

gain access to Westminster Hall.

Not all those who had received invitations to the service received

invitations to the reception in Westminster Hall. Each VC or GC holder was

accompanied by up to three guests and deceased VC and GC recipients were

also represented by up to three guests. There were a number of other

invited guests, politicians and VIPs. Once inside the gates of the

precincts of Westminster Hall there was a relative calm and the guests

formed an orderly queue to enter.

The Queen arrived at Westminster Hall in her maroon Daimler which first

saw service in 2002 for her Golden Jubilee celebrations. The Lord Great

Chamberlain, the Marquess of Cholmondeley and Colonel Stuart Archer,

received her Majesty.

Once in the Hall there was a great crush of people and it was difficult to

move about. An army of white-clad waiters and waitresses provided a

constant supply of food and beverages. The walls were decked with large

murals of the VC and GC. The Hall is a rather dark and forbidding place

with little natural light. Even with artificial light it had a gloomy

appearance. Apart from its size, it is because of the Hall's sombre nature

that it has been used on so many lying-in-state occasions.

The Queen, Patron of the VC and GC Association, received applause as she

walked down a red carpet and was presented to a number of special guests

by Mrs Didy Grahame MVO, Secretary of the VC and GC Association. The

proceedings in the Hall were informal. There were no speeches or programme

and just one short announcement. A number of the elderly or infirm VC and

GC holders took to seats and were surrounded by friends and well wishers.

On the stage at the back of the Hall the orchestra of the Irish Guards

played popular melodies but at the beginning of the reception their notes

were drowned out by the conversation of the guests. Official photographers

in smart suits moved about the Hall doing their work. At about 2.30 pm

coaches arrived for some guests and the Hall began to empty and by 3.00 pm

the reception was over.

The Guardian of 15 May 2003 reported the evaluation of one VC holder and

one GC holder. John Cruickshank VC said of the memorial: "It is

magnificent, but it could have been done before now." But Alf Lowe GC

said, "I think the reason there's been no memorial before is because the

majority of us would not have initiated it ourselves. We're rather

reticent." An Australian newspaper recorded the comment of Mr Keith Payne

VC, a Vietnam veteran who said: "It's a little overdue but it's an

appropriate time with the world situation so uncertain at the moment".

The Daily Mail reported that for two women, it was a particularly poignant

occasion. Mrs Sara Jones, widow of the late Colonel 'H' (Herbert) Jones VC

said: "It would have been H's birthday today. He'd have been 63 so it's

good timing and it's been a wonderful day."

As the mother of the late Sergeant Ian McKay VC, Mrs Freda McKay also felt

deeply moved: "I must be the only VC's mother here and I have met some

lovely people." Both women were a present reminder of the exacting toll of

war and the fact that many of the VC and GCs were awarded posthumously.

This thought was echoed during the Service in the final words of the

reading from Thucydides:

"For this offering of their lives, made in common by them all, they each

of them, individually received that renown which never grows old, and for

a sepulchre, not so much that in which their bones have been deposited,

but that noblest of shrines wherein their glory is laid up to be eternally

remembered upon every occasion on which deed or story shall call for its

commemoration. For heroes have the whole earth for their tomb."

The VC holders present were:

Capt Richard Annand

Flt Lt John Cruickshank

Lt. Cdr Ian Fraser

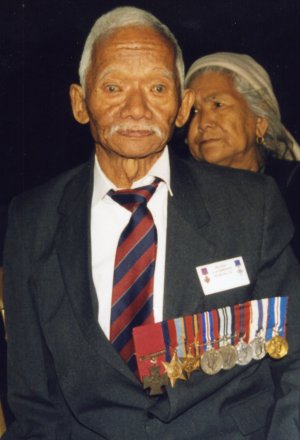

Havildar Lachhiman Gurung (Pictured)

Capt Rambahadur Limbu

Mr Keith Payne

Sub Major Umrao Singh

Mr Ernest Smith

Mr William Speakman

Sir Tasker Watkins

Lt Col Eric Wilson

Total: 11 out of 15 living recipients

The VC holders unable to attend were Bhanbhagta Gurung, Edward Kenna,

Gerard Norton and Tulbahadur Pun.

The GC holders present were:

Col Stuart Archer

Mr John Bamford

Mr James Beaton

Lt Cdr John Bridge

Lt. Col. Arthur Butson

Mr Harry Errington

Mr Kenneth Farrow

Mr Harwood Flintoff

Mr Anthony Gledhill

Mr John Gregson

Mr Derek Kinne

Mr Alfred Lowe

Mr Joseph Lynch

Mr Frank Naughton

Mr Michael Pratt

Mrs Margaret Purves

Mr Awang anak Raweng

Mr Geoffrey Riley

Mr Henry Stevens

Lt Col George Styles

Mr Charles Walker

Mr Eric Walton

Mr Charles Wilcox

Total: 23 out of 29 living recipients

The Times of 15 May lists Mr Carl Walker GC as attending, but the VC & GC

Association confirmed that he was unable to attend at the last minute

The Island of Malta and the Royal Ulster Constabulary also received the

GC. Dr. L. Gonzi, the Deputy Prime Minister of Malta and Mr Jim McDonald,

Chairman of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC Foundation represented them

at the Service.

The above list of those attending was taken from The Times, 15 May 2003.

Acknowledgements

Order of Service Programme - Westminster Abbey, 14 May 2003

The Daily Telegraph, 15 May 2003

The Guardian, 15 May 2003

The Times, 13 and 15 May 2003

The Daily Mail, 15 May 2003

The Evening Standard, 14 May 2003

Terry Hissey and Derek Hunt for their contributions and helpful comments

Rebecca Lee for drafting assistance

Memorial Video and Booklet

The video of the service and reception is available at £12 per copy and

the VC and GC Memorial Booklet is available at £2.50 per copy from The VC

and GC Association, Horse Guards, Whitehall, London SW1A 2AX. Tel 020 7930

3506 Fax 020 7930 4303.

THE

TRUE STORY OF JAMES GORMAN VC

by

Harry Willey, New South

Wales, Australia

Captain of the

Afterguard JAMES GORMAN VC.

Second Mate, NSS VERNON

This

Portrait was presented to James Gorman VC.

on his leaving the NSS

"Vernon" by the boys of the ship as a token of their regard

Artist

unknown; Photo by Harry Willey.

Original portrait donated by Marjorie

Willey

to Naval Collection, Spectacle Island

INTRODUCTION

I first became interested in

the Crimean War Victoria Cross recipient, James Gorman, when I was shown a

portrait of him by my future father-in-law, who had been married to one of

Gorman's six grand-daughters. The family, who owned the VC medal group,

were justly proud of their ancestor and believed he had been awarded his

Cross for saving the life of Captain Lushington at the Battle of

Inkermann.

Subsequent investigation threw up a mystery in the form

of another James Gorman, who had changed his name from Devereaux when

joining the Royal Navy. This Gorman/Devereaux had been born in Suffolk in

1819, whereas the true James Gorman had been born on 21 August 1834 in

Islington. The latter joined the Navy in 1850 and was serving on HMS

Albion at the outbreak of the Crimean War. It is probable that

Gorman/Devereaux was a rating on the Beagle when the call came for

the Navy to supply a Brigade to help in the bombardment of Sebastopol.

On 26 October 1854, the day after the ill-fated Charge of the

Light Brigade at Balaclava, a strong Russian force attacked the right

flank of the British siege position before Sebastopol. Disregarding an

order to spike his gun, Acting Mate William Hewett and three naval

gunners, including Gorman/Devereaux, kept such a rate of fire at close

range, that the Russians were forced to withdraw. For his steadiness in

the face of the enemy, Hewett was awarded the Victoria Cross.

It

was for this action that the bogus James Gorman claimed to have also been

awarded the Victoria Cross and many have genuinely believed his was

entitled to such an award. After all, he had faced the same danger as

Hewett and received nothing. Whatever his grievance, he was not entitled

to the Victoria Cross and, whether deliberately or through a

misunderstanding, he managed to convince enough people of this claim that

successive reference works accept him to be the rightful James Gorman.

One of the reasons the bogus Gorman was not exposed was that the

true recipient had made his home on the other side of the world,

Australia.

With the help of friends who researched the primary

sources in England, and my own research of the well-recorded life and

death of James Gorman VC, following his emigration to Australia in 1863, I

have been able to write the following story.

His Life in the

Navy

Captain of the Afterguard, JAMES GORMAN VC was born in

Islington, Middlesex, on 21 August 1834 to Patrick James Gorman, a

nurseryman, and his wife Ann (nee Furlong). They had been married at the

famous St. Martin's in the Field Church, Westminster, on the 23rd of

November 1829. When he reached the age of thirteen, James was one of the

first group of two hundred boys to be accepted into the Royal Navy as

apprentices.

He entered HMS Victory as a boy second class

on 2 March 1848. The old 2164 ton Victory had been Nelson's

flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar but, with the advent of steam, he had

been relegated to a training ship thus avoiding the fate of most of the

obsolete sailing warships, which were used as prison hulks, floating

stores or just broken up.

At the completion of six months'

training on board the HMS Victory, Gorman was transferred with

sixty-one other apprentices to HMS Rolla, a paddle wheel and sail

tender to Victory. She was a "Cherokee" Class 10 gun brig

sloop of 231 ton that had been completed in 1829 in Plymouth Dockyard. The

Apprentices cruised the choppy waters of the Channel on the Rolla

until they were declared fit to go to sea.

Gorman gained

recognition as a good seaman and was kept beyond his allotted time on

HMS Rolla to work as an Instructor for the second intake of

apprentices. At the completion of his duty on HMS Rolla he was

transferred to Dragon for only a short period from 13 September

1849 till 1 November 1849, before he was transferred to Howe where he

stayed until 12 July 1850.

He then transferred from Queen

(a floating barracks) to HMS Albion, his first ship as a boy first

class on 13 July 1850. Records show that at that time he was 5ft 2in

(155cm) tall, with blue eyes, had light brown hair and a ruddy complexion.

It was also noted that he had been vaccinated against smallpox.

James was promoted to Ordinary Seaman 2nd Class on 13 May 1852,

then further promoted to Able Seaman two months later. During the Crimean

War, he was a member of The Naval Brigade from the 1st October 1854 to 9

September 1855.

The Naval Brigade consisted of 1020 officers and

men from HMS Albion, Britannia, Bellerophon, Diamond, London, Queen,

Rodney, Trafalgar and Vengeance, who were under the Command of

Captain Stephen Lushington of the Albion.

The Naval Brigade

had been formed at the request of Lord Raglan who had asked the Navy for

assistance. At first the sailors only worked around the camps in a

non-combatant role. Then, as more of the soldiers were either killed or

wounded, they were replaced by the sailors.

The Crimean War was

the first time correspondents had been allowed to report first hand from

the battlefield. They sent their eyewitness accounts of the conflict to

the London Newspapers. The reports by William Howard Russell of The

Times were thought to be the most graphic. In describing the Battle of

Inkermann, Russell had quoted Lushington's own words: "It had commenced

at half past seven on a cold misty morning and was a determined attempt by

the Russians to force the British from the heights above the town of

Sebastopol. A long day of heavy fighting followed and the Russians were

eventually driven back."

In the Right Lancaster Battery, where

eleven days before Hewett had won his VC, the British were suffering heavy

casualties as the massed grey ranks of Russians advanced up the Careenage

Ravine.

Among the acts of bravery Russell reported was the

determination of five sailors from the Albion. These sailors, when

ordered to withdraw and leave the wounded, were reported to have replied

"They wouldn't trust any Ivan getting within bayonet range of the

wounded". The five sailors then mounted the defence works

(banquette) and kept up a continual and rapid rate of firing which

drove the enemy back three times. They were helped by wounded soldiers who

lay in the trench beneath them, who kept a constant flow of reloaded

rifles for their bluejacket comrades. Because of their exposed position,

the inducted infantrymen came under heavy fire, which swept the top of the

parapet and two of the sailors fell dead. This left the surviving three

sailors, James Gorman, Thomas Reeves and Mark Scholefield, to hold the

Russians at bay. The Russians advanced to within forty yards of the

battery before the steady fire from the naval trio finally caused the

attack to stall and the enemy began to retreat.

On the 7 June 1856

the three surviving sailors, Gorman, Reeves and Scholefield were

recommended by Sir Stephen Lushington to Queen Victoria as being worthy

recipients of the Victoria Cross. On the 24 February 1857 their names

appeared along with the names of 83 others upon whom the Queen had

conferred this honour. The Queen presented his decoration to Thomas Reeves

in Hyde Park, London, on 26 June 1857. On the same day, two Victoria

Crosses were dispatched by the War Office to be presented to Gorman and

Scholefield who were both serving in the China War.

Reeves and

Scholefield had little time to enjoy the fame of their awards; the former

died in 1862 and the latter at sea on 1858.

Gorman's Victoria

Cross was one of fifteen awarded for the Battle of Inkermann. His service

medals at this time were the Crimea Metal with Clasps for Inkermann &

Sebastopol, and the Turkish Crimea Medal, which was presented to him by

the Sultan of Turkey. He subsequently receive the 2nd China Medal with the

Canton 1857 bar.

The Metals Awarded to James

Gorman VC

Photo by Harry Willey, c1993

Gorman left

HMS Albion on 5 January 1856 with a "Very Good Conduct" report and

the following day signed on HMS Coquette as an AB. HMS

Coquette was a 670 ton wooden screw steam gun vessel of 200

horsepower, carried 4 guns and had a top speed of 10.8 knots. She had been

built by Green Blackwall on the Thames in 1855.

On 17 March 1856,

Gorman was transferred to Haslar Hospital in Gosport, Hampshire where he

was hospitalised with "rheumatism" for six weeks. When discharged from the

Hospital on 2 May 1856 he returned to HMS Coquette from where he

was discharged from Her Majesties Service three weeks later. For just a

fortnight, Gorman was a civilian ashore, until he re-enlisted for duty on

HMS Elk when the sloop was commissioned at Chatham. HMS Elk

was a brig sloop of 12 guns, having been built at Chatham Dockyard in

1847. She was 105ft long and 482 ton. It was one of the first ships of the

Royal Navy to become part of the Australia Station of the Royal Navy.

It was on 31 March 1857 while serving on HMS Elk that

Gorman received his first payment of the pension of £10 per year that had

been granted to recipients of the Victoria Cross. He received a payment of

£24 and eleven pence, the pension having been back-dated to 5 November

1854. Following this initial payment, Gorman received a quarterly payment

of £2 pounds and ten shillings for the rest of his life.

During

his service on HMS Elk, he took part in operations in the Canton

River at the taking of Fatchan and Canton from 28 December 1857 to 5

January 1858. Promoted to Captain of the Afterguard of the Elk,

James Gorman VC visited Australia on three occasions. Sydney on 31

December 1858 and again in January 1860, also calling at Melbourne in

March 1859. James Gorman VC was Paid Off at Sheerness on 21 August 1860,

his 26th Birthday, at which time he was recorded as having grown 3 inches

to become 5ft 5in (162.5cm) in height.

For the story of his

fascinating life in Australia, read the full account in the Journal of the

Victoria Cross Society

SOUTH

DEVON PAYS TRIBUTE TO TWO VC HEROES

Two

Victoria Cross recipients from the neighbouring riverside communities of

Dartmouth and Kingswear were honoured in two ceremonies that took place,

appropriately, on Remembrance Sunday, 10 November and Armistice Day, 11

November 2002. In what may be a unique event in the recent honouring of

Victoria Cross holders, two such ceremonies were held within 24 hours of

each other in the communities which face each other across the River Dart.

Local

publisher Richard Webb and author Don Collinson discovered that there were

no memorials to Corporal Theodore Veale of Dartmouth or Lt Col H. Jones of

Kingswear.

It was

rather poignant that, in a traditional Royal Navy community, both VCs were

awarded to soldiers, albeit members of the Devonshire - later the

Devonshire and Dorset - Regiment. The next two years were spent

researching, organising and seeking funds for the memorials.

DARTMOUTH

Sir Ray

Tindle, the owner of the Dartmouth Chronicle, as well as a former member

of the Regiment, helped to make the event possible. Similarly, the Jones

family donated funds for the memorial to the Falkland's hero.

Sunday 10

November 2002 was a wet and blustery day that did little to dampen the

spirit of those who witnessed the ceremony in one of Britain's most

picturesque towns. In a moving ceremony at Royal Avenue Gardens, Sir Ray

Tindle paid tribute to Corporal Veale: "Teddy Veale served his country as

did many others in that war in which a million and a quarter British men

and women were lost.

'We

remember them all today, but Teddy Veale risked his life over and over

again to save another. 'His bravery was beyond the call of duty. That is

why we are placing this plaque here in this public place. He will never be

forgotten by his town or his regiment."

Sir Ray

went on to read the citation that appeared in the London Gazette of 9

September 1916:

"For most

conspicuous bravery. Hearing that a wounded officer (Lt.Eric Savill) was

lying out in front, Private Veale went out to search, and found him lying

amidst growing corn within fifty yards of the enemy. He dragged the

officer to a shell hole, returned for water and took it out. Finding that

single-handedly he could not carry the officer, he returned for

assistance, and took out two volunteers. One of the party was killed when

carrying the officer, and heavy fire necessitated leaving the officer in a

shell hole. At dusk, Private Veale went out again with volunteers to bring

in the officer. Whilst doing this an enemy patrol was observed

approaching. Private Veale at once went back and procured a Lewis gun, and

with the fire of the gun he covered the party, and the officer was finally

carried to safety. The courage and determination displayed was of the

highest order."

Mrs

Theodora Grindell, Corporal Veale's daughter watches as Miss Jennifer

Grindell, his granddaughter lays a wreath.

Officers,

men and old comrades of Corporal Veale's regiment then marched to the war

memorial accompanied by the Regimental Band of the Devonshire and Dorsets.

People lined the town's streets before gathering to witness the

traditional wreath-laying ceremony.

Corporal

Veale's daughter, Mrs Theodora Grindell then unveiled the memorial.

Finally, there was a Remembrance service held at St Saviour's Church.

Teddy Veale died a few days short of his 88th birthday on 6 November 1980

and was cremated and his ashes scattered at Enfield Crematorium.

A memorial

to this brave man was long overdue and it was appropriate that his

hometown should honour him.

KINGSWEAR

The

following day, another ceremony took place on the opposite bank at

Kingswear. About 100 onlookers, dignitaries and representatives of the

Parachute Regiment and the Devonshire and Dorset Regiment joined Mrs Sara

Jones and her family in the unveiling of a memorial plaque on the ferry

slipway.

H.Jones's

brother, retired Royal Navy Commander Timothy Jones, delivered a eulogy in

which he preferred not to dwell on his brother's sacrifice, but rather

about his love of Kingswear: "We're not here to remember that bleak

hillside in the Falklands, we're here to remember the man, how much he

loved Kingswear and how much he enjoyed growing up here."

He related

some anecdotes from their childhood, which highlighted the future VC's

sense of daring and adventurous spirit:

"We had a

great childhood and we really enjoyed ourselves, although with the

exuberance of youth we did overdo it sometimes. As growing boys we were a

real trial to our parents and the local bobby, PC Bailey. But life was

always exciting when H was around."

On 11

October 1982, the London Gazette published the following citation: On 28

May 1982 Lieutenant Colonel Jones was commanding 2 Battalion The Parachute

Regiment on operations on the Falkland Islands. The Battalion was ordered

to attack enemy positions in and around the settlements of Darwin and

Goose Green.

During the

attack against an enemy who was well dug in with mutually supporting

positions sited in depth, the Battalion was held up just South of Darwin

by a particularly well-prepared and resilient enemy position of at least

eleven trenches on an important ridge. A number of casualties were

received. In order to read the battle fully and to ensure that the

momentum of his attack was not lost, Colonel Jones took forward his

reconnaissance party to the foot of a re-entrant, which a section of his

Battalion had just secured. Despite persistent, heavy and accurate fire

the reconnaissance party gained the top of the re-entrant, at

approximately the same height as the enemy positions. From here Colonel

Jones encouraged the direction of his Battalion mortar fire, in an effort

to neutralise the enemy positions. However, these had been well prepared

and continued to our effective fire onto the Battalion advance, which, by

now held up for over an hour and under increasingly heavy artillery fire,

was in danger of faltering.

In his

effort to gain a good viewpoint, Colonel Jones was now at the very front

of his Battalion. It was clear to him that desperate measures were needed

in order to overcome the enemy position and rekindle the attack, and that

unless these measures were taken promptly the Battalion would sustain

increasing casualties and the attack perhaps even fail. It was time for

personal leadership and action. Colonel Jones immediately seized a

sub-machine gun, and, calling on those around him and with total disregard

for his own safety charged the nearest enemy position. This action exposed

him to fire from a number of trenches. As he charged up a short slope at

the enemy position he was seen to fall and roll backward downhill. He

immediately picked himself up, and again charged the enemy trench, firing

his sub-machine gun and seemingly oblivious to the intense fire directed

at him. He was hit by fire from another trench, which he outflanked, and

fell dying only a few feet from the enemy he had assaulted. A short time

later a company of the Battalion attacked the enemy who quickly

surrendered. The devastating display of courage by Colonel Jones had

completely undermined their will to fight further.

Thereafter,

the momentum of the attack was rapidly regained, Darwin and Goose Green

were liberated, and the Battalion released the local inhabitants unharmed

and forced the surrender of some 1200 of the enemy.

The

achievement of 2 Battalion The Parachute Regiment at Darwin and Goose

Green set the tone for the subsequent land victory on the Falklands. They

achieved such a moral superiority over the enemy in this first battle

that, despite the advantages of numbers and selection of battle-ground,

they never thereafter doubted either the superior fighting qualities of

the British troops, or their own inevitable defeat. This was an action of

the utmost gallantry by a Commanding Officer, whose dashing leadership and

courage throughout the battle were an inspiration to all about him.

Mrs Jones

said that the Kingswear tribute meant a great deal to the family as, "Of

all the things that have been done over the years to commemorate my

husband's bravery, this is possibly the most wonderful. There is already a

memorial in the church, but I think this is particularly poignant and will

be a reminder to all of us whenever we board the ferry. This was a part of

the world that my husband loved and he had hoped to retire

here."

(1) Three

Devonians won the Victoria Cross in the First World War, rejoicing in the

names of Veale, Sage and Onions.

The

unveiling of memorial to Col. H. Jones VC by Mrs Sara Jones and Commander

Timothy Jones

|